Can the UK become a global life sciences superpower?

The latest report from Public Policy Projects and IQVIA highlights a unique opportunity to propel UK life sciences and pharma to new heights.

The rapid deployment of Covid-19 clinical trials and the success of vaccine development has left many experts wondering: why has this speed, efficiency and collaboration not dictated UK life sciences policy till now? Can this country capture the innovative spirit which has defined its response to Covid-19 and use its exit from the European Union as an opportunity to become a life sciences superpower?

These were just some of the questions that were addressed in September as IQVIA and Public Policy Projects (PPP) launched their latest report: Putting Policy into Practice: Making the UK a Global Life Sciences Superpower.

The report combines extensive life sciences stakeholder surveys from IQVIA with a detailed policy overview from PPP. Its conclusions and recommendations provide a practical and pragmatic blueprint to expand the sector – paying special focus to the combined impacts of Covid-19 and Brexit.

Progress in the face of unprecedented challenge

Both the webinar and the report itself shared an immense sense of pride over the UK life sciences achievements of the past two years, including the development of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine.

“The name with which we refer to as the ‘Oxford AstraZeneca Vaccine’ actually disguises the partnership which put it together,” explained Tom Roach, AstraZeneca’s UK President, “this vaccine was only possible because of extensive collaboration across the life sciences sector – from organisations such as the MHRA, COBRA, SES, the Vaccines Task force and of course, the NHS.”

With ongoing genomic sequencing working to identify new Covid variants, the rapid development and deployment of this vaccine is one demonstration of the UK’s unique end-to-end research process in action.

The successful response of UK life sciences to the pandemic has not gone unnoticed by pharma and life sciences stakeholders globally. IQVIA’s latest global survey on the perceived attractiveness of the UK, featuring feedback from over 200 c-suite pharma and biotech executives, suggests that the UK remains a crucial launch location for new medicines. According to the findings, 79 per cent of stakeholders believe that the UK will remain a priority launch country for new medicines – with 77 per cent of the same cohort stating that this had historically been the case.

“These figures highlight a tremendous success story for UK life science policy and a growing sense of attractiveness of the UK for conducting trials and launching medicines,” said Angela McFarlane, IQVIA’s Vice President, Strategic Planning, North Europe.

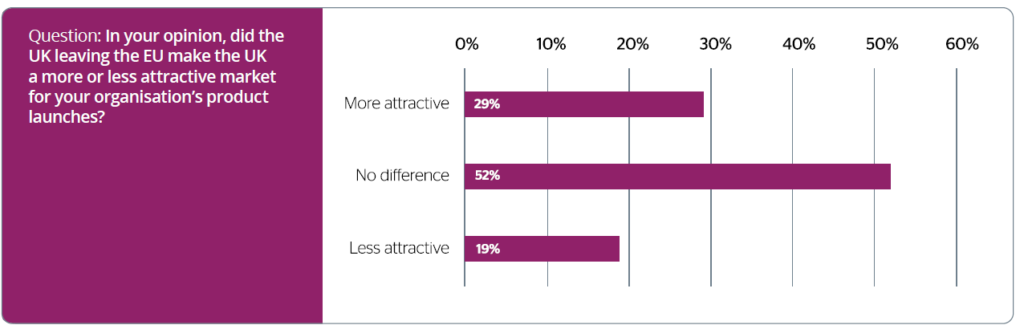

The perceived impact of Brexit also features heavily in the report (see figure 1 below). Promising for the sector is that, rather than weaken the UK’s position in this highly competitive market, c-suite executives have noted that Brexit could potentially come with a reduction in bureaucracy and regulation. The report states that 81 per cent of life sciences and pharma stakeholders believe that leaving the EU has made the UK at least the same or a more attractive destination for medicine launches. This, Angela stressed, is great news for the sector – a reduction in red tape, supplemented with enhanced government support could improve the UK’s standing as a life sciences and research innovation hub.

Further enhancement of the UK’s global life sciences standing stems from its regulatory framework. 65 per cent of respondents were aware of the latest activity from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) with 34 per cent confirming the organisation as their “primary regulator”. Participating in the webinar, Dr June Raine, Chief Executive of the MHRA highlighted the organisation’s innovative “end to end regulatory process”.

While warning against complacency, Dr Raine was keen to stress that the ambition of being first choice regulator for global pharma and biotech is “within reach”. Achieving this goal, she argued, will help facilitate a “tsunami of life sciences innovation” in the coming months and years.

A vibrant policy environment

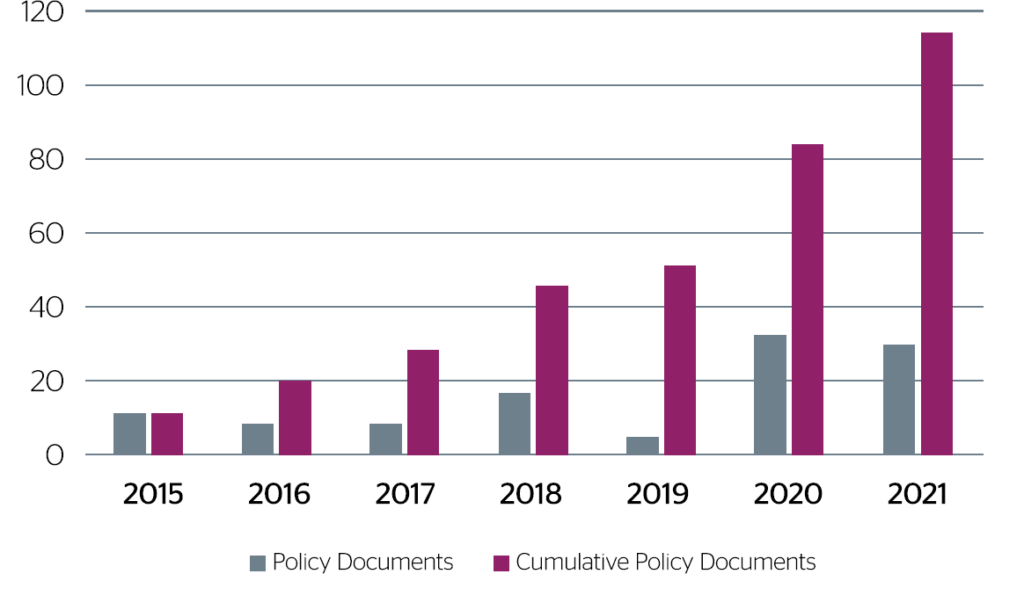

The challenge for policy makers is to build on this position of strength and develop UK life sciences into a globally mobile industry. Over the last few years, UK government agencies published a total of 114 policy documents (illustrated by figure 2 below) designed to address and improve the attractiveness of the UK Life Sciences sector in a globally competitive market.

Optimism in the UK market from key stakeholders combined with an active policy environment can help ensure that the “tsunami of innovation” is felt by the people who need it most, the patients.

A shrinking window of opportunity

These findings provide a snapshot into the UK life sciences sector with apparently limitless potential. However, demonstrating potential and capitalising on it (i.e. putting the policy into practice) are two distinct goals.

As Angela had previously warned, the “window of opportunity” presented by an optimistic market and a seemingly enthusiastic policy base, will not be open forever. “We feel the optimism of the IQVIA survey,” said AstraZeneca UK President Tom Roach, “but the UK has consistently suffered from a historical lack of success in turning rhetoric into action.”

Despite its enviable end-to-end research capacity and innovative regulatory framework, the UK has long suffered from an “adoption problem” when it comes to new medicines and therapeutics. Tom pointed to the decrease in UK life sciences exports and research levels in recent years. “In vital areas such as data integration, even countries like Scotland, Estonia, Sweden and Iceland are in fact leagues ahead of us. Without increasing UK competitiveness in these areas the sector will fall short of true ‘global competitiveness’”.

For all the positives to be taken out of the UK’s research response to Covid-19, the pandemic has still caused a substantial drop off in non-Covid clinical research. This was already in steady decline prior to the pandemic with the UK dropping from third in the world for exports almost six years ago to seventh in 2020. The UK today only accounts for two per cent of the global total for clinical research. “Let’s catch up on re-establishing services following the pandemic,” said Tom, “but we must leap ahead in our treatment of chronic disease, diagnostic pathways and integrating our approaches to data.”

Dr Louise Wood, Director, Science, Research & Evidence, Department of Health and Social Care, described the juxtaposition between rhetoric and action, stating that: “we know what needs to be done, but have hesitated at the point of action.” Louise called for greater decisiveness on the part of UK life sciences to capitalise on what she described as an “unprecedented consensus” amongst key stakeholders. “We must be bold and cut through political reluctance,” she stressed.

“The NHS needs to be included as a crucial participant of life sciences, of core workstreams, timelines and working groups,” said Louise, who lamented previous indecision that has prevented the NHS from taking a more central role as an innovation partner.

“The exam question is taking the opportunity presented by Covid-19 and creating a long-lasting global life sciences hub in this country”

Seizing the moment

For all the potential of its life sciences sector, the UK has fallen short of what can be described as true global leadership. Accordingly, Putting Policy into Practice does far more than praise the UK life sciences. More fundamentally, the report is a callout to the UK government to build on this position of strength and deliver innovative treatment to patients. There is a unique opportunity to do so. Not only has the Covid-19 experience galvanised the life sciences community, but the development of Integrated Care Systems presents a chance to grapple life sciences processes and enhance care delivery.

“This country is still capable of doing great things,” insisted Tom, “but the exam question is taking the opportunity presented by Covid-19 and creating a long-lasting global life sciences hub in this country.” As Tom went on to say, the UK must create an environment for industry to grow and patients to benefit, turning the life sciences sector from strategic forum to delivery and innovation hub.

Key recommendations of Putting Policy into Practice: Making the UK a Global Life Sciences Superpower

- The Life Sciences Council should be given the responsibility to carry forward the partnership model that evolved during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- The Life Sciences Council should be obligated to issue a report each year on UK life sciences development. This report should be presented to Parliament by government members of the council.

- The annual report to Parliament from the Life Sciences Council should include a chapter that reports the progress of implementing the 30 recommendations of the Public Policy Projects Clinical Research Coalition.

- The annual report should include a chapter that reports on the progress of implementing the recommendations of the Public Policy Projects Rare Diseases Coalition.

- The UK should develop a coherent policy for using health data to improve outcomes for citizens, this policy should become a cross-government priority.

- The new management team at NICE should continue to build on the Five-Year Strategy and continue as an active member of the Like Sciences Council.